Sri Lanka and What I Didn't Know

- pavethra

- Feb 11, 2021

- 5 min read

Over a month ago, through countless reshares across social media I felt compelled to read on the destruction of a memorial erected at the University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Without reading, the pictures themselves spoke for the sorrow and profound anger within the students and countless Tamils. The images revealed Sri Lankan authorities guarding the gates of the university and a bulldozer peacefully tearing away the Mullivaikkal memorial that once allowed Tamils to constantly remember the hundreds and thousands of innocent Tamil civilians who were barbarically tortured and killed during the 2009 civil war.

Many peered through the university gates with despair struck in their eyes. Many participated in a sit-in protest - eager to have the answers to their questions. Many joined in a hunger strike and demanded the reconstruction of the monument. Two were warned that"they will be dealt with" for trespassing on the university campus and starting a riot. This rage rippling through the community is a clear sign of no longer being able to watch the Sri Lankan government pull-down Tamils.

As I saw this rage pour into social media, I too wanted to share this on my account but something stopped me each time I tried to push down the "your story" button.

My limited knowledge of the Sri Lankan civil war left me with an abundance of guilt. I knew this feeling would only wear away with more reading and active participation in such conversations.

As a child of immigrant parents, I remember hearing conversations on the war within my parents and watching their reactions to what they heard from my family in Sri Lanka. It became easy for any child to understand that there was something very wrong. I can recollect a documentary on the brutality of the war being played in the living room and no one uttering a word. However, with time the conversations around the civil war fell silent within my home and, soon, my intentions to start the conversation fell.

Until, the recent news on the destruction of the memorial and the report from the UN Human Rights Council highlighting the island's constant failure to address war crimes and crimes against humanity in the final years of the war left me feeling deeply concerned, impatient, and wanting to research more.

In 1975, the formation of The Liberation of Tamil Tigers, also known as Tamil Tigers, started to emerge as they fought for an independent state in the island's north and east. The formation of such a group was a product of discrimination and violence, including sexual violence, towards the ethnic minority Tamils by the Sinhalese. With many anti-Tamil pogroms, regulations on university admissions to limit Tamil's receiving higher education, and the burning of the Jaffna Public Library by Sinhalese extremists, helped by the Sri Lankan police, it was no surprise when the civil war erupted in 1983. In 2008, when government forces were threatening the Tiger's capital, Kilinochchi, it could be foreseen that the worst was yet to come.

While I looked for further reading, I found the documentary that once made the house enter stillness - Sri Lanka's Killing Fields, 2011. As I pressed play, I knew that this silence was going to fall over me again.

The documentary revealed the relationship between position, power, and responsibility. I say this primarily because I can see how the Sri Lankan government convinced the UN representatives within Sri Lanka that their safety could no longer be guaranteed. Whilst this may have been true, the following deliberate attacks on innocent civilians spoke for their aim to remove international witnesses.

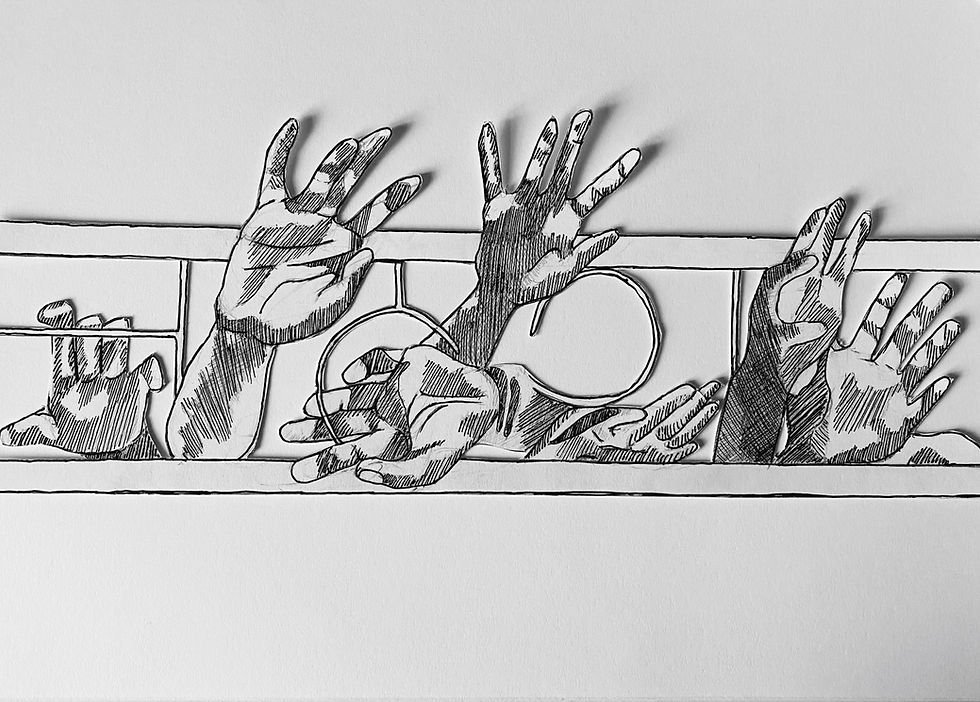

Countless civilians stretched their arms through the gate, which separated them from the UN members, and waved their hands uncontrollably - begging for them to stay. Some children peered through the gate with a feeling of utter abandonment. Sorrow and fear spread through the community as the representatives drove away.

This clip within the documentary demonstrates the power of international communities in revealing the unheard voices of civilians and their ability to bring justice. Using various screenshots from this clip as a reference, I decided to develop the artwork below.

This drawing and paper cut-out focuses on movement. The bold lines call attention to the motion of hands waving and calling for helping. Where the shadows created by the cut-out are unintentional, they add an element of reality and help to replicate the urgency within the civilians. It felt important to capture this clip into a drawing as it brings reminders of how many civilians were cast aside at a time of deep fear and unthinkable uncertainty for their future.

One of the most horrifying aspects of the civil war includes the 'No fire zone'. The Sri Lankan government announced this zone as zero civilian casualties. In this area, emergency hospitals and a make-shift arrangement of beds and mattresses, in a primary school, were organised. Red-crosses on the roof of this building suggested that, under international law, it was protected from shelling. This encouraged hundreds and thousands of desperate civilians to flee into what appeared as a safe zone.

Little did they know that this left the government forces an open path to cause a deliberate attack on as many as 400, 000 Tamils. The government's approach to maximise casualties did not stop here. After each shell, a second shell followed; this ploy meant that anyone who helped the injured was also in extreme danger. The core principle of war is to protect civilians and only target military objectives. Both of which were clearly not met.

This so-called 'no fire zone' was moved and constantly diminishing in size. From a 7-mile-long area to just one square mile size with no food and water. Although the military forces hold an obligation to ensure that the civilian population is not starved, many were in deplorable conditions.

In what already is an unimaginable situation, the execution of prisoners, torture, and rape elevate the heights of this massacre. The heart-rending 25-year civil war between government forces and the Tamil Tigers came to a close in May 2009 after the killing of Velupillai Prabhakaran, leader of Tamil Tigers.

Today, the island's physical appearance lures us into the belief that it has recovered from the brutal war. However, beneath this pretty picture is the discrimination and oppression that once triggered a war.

Till today, the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) from 1979 persists. This grants the Sri Lankan authorities the power to arrest anyone, merely, based on suspicion of terrorism. It goes without any surprise that this has law has been misused to arbitrarily arrest Tamils.

In February 2020, the Sri Lankan government declared that it will no longer collaborate with the UN Human Rights Council and, therefore, landmark resolution 30/1. This resolution advocates 'reconciliation, accountability, and human rights'. The government proposed that it will conduct its 'own reconciliation and accountability' procedure. However, the 146, 679 people reported missing, destruction of Hindu temples, and denial of remembrance events

say otherwise.

Movements such as the Pottuvil to Polikandi, P2P, protest in Sri Lanka represents the concept of both tiredness and anger within countless Tamils and Muslims. A myriad of Tamils outraged by the number of enforced disappearances and a multitude of Muslims battling against the forced cremation of Muslims, who died due to COVID-19. Where this protest demonstrates unity, it also represents the number of people living under tyranny.

It is almost 12 years on from the end of the civil war and, still, many survivors and Tamils across the globe are searching for answers - to unpunished war crimes, the right to remember the war dead, and numerous disappearances.

By writing this post, I have been able to revive the conversation on the Sri Lankan civil war at my home. I hope that with prolonged reading and listening, I can sustain this conversation and carry it onto the people around me.

We must remember that mass remnants of the genocide persist, even today.

Comments